By Matthew Ari Elfenbein

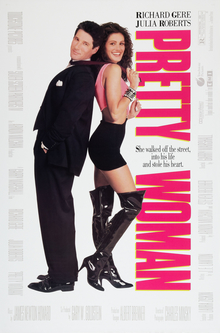

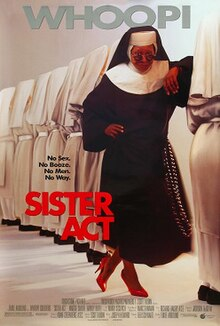

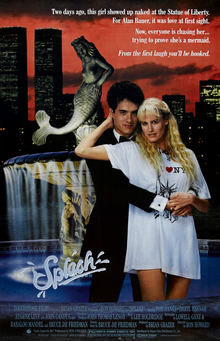

Fig. 1: Four Touchstone films Pretty Woman (1990), Dead Poets Society (1989), Sister Act (1992), and Splash (1984).

The values and family-friendly wholesomeness of Disney probably do not conjure up ideas of gazing upon Julia Roberts’ underwear, Ethan Hawke cave drinking in a schoolboy outfit, Tom Hanks smuggling naked girls around New York, or Whoopie Goldberg bringing soul to a group of singing nuns. Yet, this became a landmark of popular culture for Disney’s teenager-focused production company, Touchstone Pictures (formerly Touchstone Films from 1982-1984).

Carpe diem, seize the day, was not simply muttered by Robin Williams but is precisely what Disney attempted to do when catering to the new crowds looking for violence, sex, and promiscuity with the overabundant 1980s flare (and oversized hair). The following aims to explore Touchstone Pictures’ attempt to garner a new mature fan base while demonstrating audiences' shifts in generational sensitivities and expectations.

Moving into a New Generation

In 1984, Disney’s film output largely remained in the live-action films with family-friendly narratives and scatterings of animated features. This model had trouble connecting with movie-going audiences, especially teenagers and adults. The films featured stories that included inspiration, magic, and a wholesome nature that was good for families with young children. Concurrently, the 1980s transitioned from the matured Generation X to the impressionable Millennials. America seemingly moved into the shopping mall, listened to hip-hop music, and consumed media through emerging home video markets. The multiplex theaters located inside these malls and suburbs increased the visibility of the movies and the experience of new imaginative worlds. Disney had to reimagine their appeal and reach these audiences, especially those who strayed from the cartoons and watered-down horror that once thrilled them.

Before leaving the Walt Disney Company, CEO Ron Miller formed Touchstone to diversify the business side of their film productions. Under Miller’s leadership and directive, he 'purchased the rights to Who Framed Roger Rabbit?,' which began development while the first Touchstone film was released when 'Splash was the studio’s first hit in over fifteen years' (Lewis 1994, 104-105).

The New Mouse in Town

While significant achievements, this new creativity diversification differed from Miller's game since he focused more on the business and corporate returns in the grand scheme. The turning point, especially with the newly formed Touchstone Films, came in 1984 when Michael Eisner became the incoming CEO, and Jefferey Katzenberg foresaw the productions of the Walt Disney Company. The bond between Disney and Touchstone, influencing each other at different points in the audience and culture, formed new conceptions of corporate relationships and ways to approach the global consumer.

One of these changes was an investment in creative voices and personalities that can tell new stories, even with Disney, before Eisner, Wells, and Katzenberg, recognizing that ‘direct appeals to younger adult audiences’ was the direction towards newfound profitability and success (Kunze 2023, 48).

This new structure and inclusion of creative touches is evident in the proliferation of a high-concept script and story, which Michael Eisner championed. This point is mainly seen with the executive’s need to ‘supply more adult-oriented films’ in a model that emphasizes ‘story, medium-budget projects, and the desire for close control and interaction with the filmmakers’ (Wyatt 1994, 89-90).

Furthermore, the formula of the story being told was the direct link to the consuming teenage and adult audience, thus finding a structure that accomplishes the edict of the high-concept, a term that Katzenberg and Eisner coined, of ‘making the movie easier to see,’ which is a convenience for these young audiences (Snyder 2005, 14-15).

Eisner focused on the guest experience, which includes how audiences engage with the filmic output. From the get-go, their goal was to bring Disney’s appeal to the new generation of audiences and guests in their theatrical and theme park industries. The target audience in the mid to late 1980s was the American teenager who, at the time, looked at Disney as producing material and experiences for children. Still, the tight ship he commanded pushed Disney and Touchstone to new realms of production in risqué markets, distribution through home video, and exhibition in the growing amounts of multiplex screens. Continuing with the co-production model that has attempted to bring new visions to the screen, the Touchstone brand was helmed as the savior to this problem that they had (Telotte 2008, 145). Touchstone provided the ability to produce films that do not have wholesome and magical sentimentality while reaping the benefits of new audiences for these adult films.

Reconstituting the Hollywood Plan

A few recurring themes become evident when looking at the extensive filmography of Touchstone Pictures, also known as Touchstone Films, from 1983 to 1986. Katzenberg ensured a blockbuster, introduced a new casting method with the model that used television stars, as well as ‘tell high-concept stories, tightly manage the budgets, avoid top stars and directors (and therefore big egos), and give priority to family-friendly fare with broad appeal’ (Kunze 2023, 117). Economical casting and productions can be seen in the case of Three Men and a Baby (1987), which featured Ted Danson and Tom Selleck as the stars. This plan also used a French narrative, assuming that foreign markets would flock to these films if domestic returns were not good.

This mentality for Touchstone sets it apart in the global market, which includes the subject matter, co-production status, theme park integrations, and other immersive experiences, and how the tone of the films changed over time until the studio's original creed seemed like it needed to be more viable from a business standpoint. Even though this studio deserves a book-length study or a deeper study of any kind, I will try to pull out these themes in an economical manner that brushes the history and output for ideas that characterize the relationship between the Disney Company and Touchstone.

The subject matter featured smoking, drinking, sex, and other activities that would not appeal to parents as family topics. However, one must think of these children’s curiosities getting the best of them. For instance, in Splash (1984), the film features John Candy's philanderer’s characterization, looking up women's skirts and enjoying a libation-filled life.

The ‘commodified as spectacle’ of sexual activities and the excitement of the naked body, especially model Daryl Hannah in 1984, depart from Disney's mostly sanitized creation of characters and plays on the pleasures of scopophilia for the audience and cinematic medium (Mulvey 2015, 22).

This sexualization is later emphasized with Jessica Rabbit's voluptuous curves and appeal in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), which presents a transition towards the heightened violence present in cartoons but mixed with reality. Touchstone blended these two spaces, fantasy and reality, through the subject and material that would make Mickey Mouse blush.

Deflating and Reimagining Touchstone’s Strategy

It is important to note that during Bob Chapek’s CEO tenure, Disney's state reverted many Touchstone films to strictly Disney properties and stories. The reliance on nostalgia, magic, and dreams, which are present in Disney’s animated catalog, was the family-friendly direction they navigated towards, thus returning to a quasi-post-Eisner period of unrelating to the older teenage audience. This shift is evident in the Disney animation output and the market’s shift towards more adult-centric material, even with older properties.

Entering the 1990s, the themes seem to settle, and hairstyles deflate; the sexual and violent nature of the Touchstone cinema still attracts audiences, which seemingly extends across the many emerging Disney products and experiences. Touchstone and Disney fostered a new era of storytelling and money-making by holding back on moral lessons and embracing the fun and joy of being socially liberated.

Touchstone’s financial and crowdsourcing models changed how independent sources could contribute to Disney's machine. Other financers and companies beyond Disney, similar to the party of corporate elites in Adventures in Babysitting (1987) or the homely crowds in the business and bars of Cocktail (1988), pooled their money to have stakes as producers. Silver Screen Partners is one of these companies that started showing up, which was made up of 'doctors, dentists, and other upper-middle-class Americans' (Gomery 1994, 80). This collective unit would have shares in Disney’s stock and returns, demonstrating the business's connection beyond creative endeavors. This collaborative nature of funding would then expand, with each successive film being attached to an increasing number of producers and financing companies.

The late 1990s and 2000s presented a turn where Touchstone expanded its co-productions by increasing collaborations with established directors and producers such as Wes Anderson and Jerry Bruckheimer. The most notable was Steven Spielberg, who helped establish DreamWorks, which is known for its animation productions. Still, it then allowed Spielberg to produce his realm of fantasy and dramatizations of actual events, which appealed to the adult taste.

Concluding an Era of Inspiration

During the 1980s, Touchstone became a director's studio, controlled by the creative visions of maturing artists and not the edgy visions presented earlier. The audience remained the same, meaning the content followed the teens from the 1980s into their adult lives through the 2010s. While the content and material changes with the demographic, it needs to include new generations of tastes, sensibilities, and intellectual properties. Disney and Touchstone had reached a stalemate, which was evident across the company and their reinvestments in nostalgic and ensured content to buy into. The director-producer relationships needed to be replaced with intellectual property that would appeal to popular culture.

Ultimately, the demise of Touchstone arose from the changing demographic and tastes of the audiences, who were no longer teenagers or young adults (Allen 2002, 16). The new Generation Z emerged as the audience of societal marketing focus, and the edgy and realistic Touchstone output was not appealing anymore. The cultural sensibility also adapted to a desensitized society of these images of smoking, drinking, and other vices on the screen. Disney had to refigure what would work from a business standpoint, especially with then (and now) CEO Bob Iger, who has a business mentality that emanates from a creative vantage point.

Somewhere, Touchstone's mission did not match or meet the expectations of the Walt Disney Company. With the physical media home release of The Light Between Oceans (2016), the lights turned off, and the smoke cleared for the legacy and momentum of Touchstone Pictures.

At one point, the company reached the stars. Still, the main takeaway is that Disney’s parenting and control of Touchstone was a creative business relationship, which eventually had to change with the culture. Nevertheless, we, the audiences, will forever be left with the images and narratives that dictated popular culture and brought prominence to the name ‘Madison’ (Polowy 2014).

Dr. Matthew Ari Elfenbein is a Visiting Instructor of Film and Media at Florida Atlantic University. His research centers on animated screendance and audience engagement with cinema, with a particular emphasis on Disney films. This focus on viewer interaction underpins his work, which is deeply intertwined with experiential learning and the educational experiences of both students and faculty. Dr. Elfenbein earned his Ph.D. from Florida Atlantic University and his M.A. from the Martin Scorsese Department of Cinema Studies at NYU Tisch.

But wait! There's MORE!

If you love all things Disney, if you had a presentation that you would love to see written down (and citable) come out into the world, email Bee! Do you have a book coming out and would love to have a launch with us? Email Bee! Did your book, or someone else's book, come out and you want to see us do a book review or an author interview...that's right, email Bee!

Check out our Want to Write for DisNet post.

(Bee's email is also disnetblog@gmail.com)

References

Allen, David. 2002. "Touchstone picture: the `long-range plan' has been rendered obsolete by the complexities of commercial change. David Allen explains the finer points of the concept that has replaced it: `the business model.'” Financial Management [UK], May 2002. link.gale.com/apps/doc/A90388119/AONE?u=gale15691&sid=bookmark-AONE.

Gomery, Douglas. 1994. “Disney’s Business History: A Reinterpretation,” in Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom. New York and London: Routledge.

Heffes, Ellen M. 2002. “Reinvigorating Mickey and Friends via New Technology,” Financial Executive 18, no. 3 (May 2002). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A85884333/BIC?u=gale15691&sid=summon&xid=488bc33b.

Kunze, Peter C. 2023. Staging a Comeback: Broadway, Hollywood, and the Disney Renaissance. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Lewis, Jon. 1994. 'Disney After Disney: Family Business and the Business of Family.' In Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom, edited by Eric Smoodin. New York and London: Routledge.

Mulvey, Laura. 2015. Feminisms: Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Polowy, Kevin. 2014. “How a ‘Splash’ Joke Lead to the ‘Madison’ Baby Name Boom,” Yahoo! (blog), March 7, 2014, https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/blogs/movie-news/splash-joke-lead-madison-baby-name-boom-190720175.html.

Snyder, Blake. 2005. Save the Cat! The Last Book On Screenwriting That You’ll Ever Need. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions.

Telotte, J.P. 2008. The Mouse Machine: Disney and Technology. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Wyatt, Justin. 1994. High Concept: Movies and Marketing in Hollywood. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Images

Fig. 1a: Four Touchstone films Pretty Woman (1990), Dead Poets Society (1989), Sister Act (1992), and Splash (1984). 'Pretty woman movie.jpg.' Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pretty_woman_movie.jpg. Accessed 18 July 2024.

Fig. 1b: Four Touchstone films Pretty Woman (1990), Dead Poets Society (1989), Sister Act (1992), and Splash (1984). 'Dead poets society.jpg.' Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dead_poets_society.jpg. Accessed 18 July 2024.

Fig. 1c: Four Touchstone films Pretty Woman (1990), Dead Poets Society (1989), Sister Act (1992), and Splash (1984). 'Sister Act film poster.jpg.' Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sister_Act_film_poster.jpg. Accessed 18 July 2024.

Fig. 1d: Four Touchstone films Pretty Woman (1990), Dead Poets Society (1989), Sister Act (1992), and Splash (1984). 'Splash ver2.jpg.' Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Splash_ver2.jpg. Accessed 18 July 2024.

Fig. 2: Mickey Mouse and Roger Rabbit looking at the 'Castle Cake''s for Walt Disney World's 25th Anniversary. @TWDCArchives. '“Castle in the Sky” In 1991, this majestic, 145-foot-high hot air depiction of #CinderellaCastle began a multi-city tour commemorating the 20th anniversary of #WaltDisneyWorld.' X.com. https://x.com/TWDCArchives/status/1665732975818932226/photo/1. Accessed 18 July 2024.

Fig. 3: The Touchstone Films Logo. 'Touchstone Pictures.' MediaNews. https://medianews.fandom.com/wiki/Touchstone_Pictures. Accessed 18 July 2024.

Fig. 4: Three Men and a Baby Theatrical Poster. 'Three Men and a Baby.png.' Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Three_Men_and_a_Baby.png. Accessed 18 July 2024.

Fig. 5: Still of Jessica Rabbit from Who Framed Roget Rabbit? Zemeckis, Robert, dir. 1988. Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Los, Angeles, CA: Touchstone Pictures.

Fig. 6: Theatrical Poster of Cocktail (1988). 'Cocktail 1988.jpg.' Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cocktail_1988.jpg. Accessed 18 July 2024.

Fig. 7: Theatrical poster for The Light Between Oceans (2016). 'The Light Between Oceans postet.jpg.' Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Light_Between_Oceans_poster.jpg. Accessed 18 July 2024.

Comments